Cost #2: Avoidance Creates and Maintains Our Symptoms

Avoidance creates and maintains the symptoms of anxiety disorders. People with OCD, for example, often check and recheck to ensure a task is complete. Studies show this checking is an active form of avoidance, with each check followed by brief anxiety reduction (“phew!”).

This is the case for most anxiety symptoms. When we worry excessively, seek reassurance, or perform repetitive rituals, a single motive is at play in the back of our mind. Symptoms we think of as anxiety are actually ways we avoid anxiety.

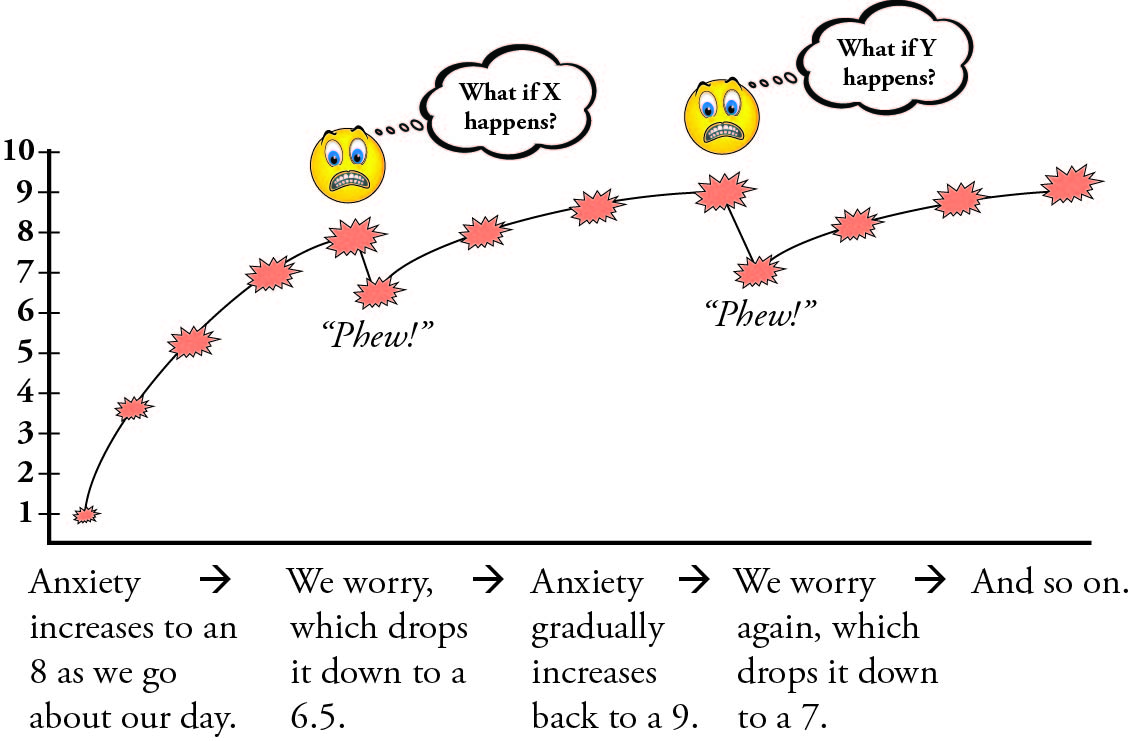

Consider the example of worry. Worry is the act of thinking about the future in a repetitive, “what if” manner. What if lose my house? What if I lose my job? You know the drill. Worry is incredibly common. And for those who worry way too much, it is a way of avoiding anxiety.

This surprising fact is well-supported by research findings. There is a device called a skin conductance sensor, for example, that measures physiological symptoms of anxiety. When anxious people worry while attached to this device, something remarkable happens. Their anxiety decreases!

The process unfolds as follows:

- Experiencing anxiety makes us feel threatened. This is especially unpleasant when anxiety is free-floating (i.e., not triggered by obvious threats) because there is nothing we can meaningfully do about it.

- Our brain responds to anxiety’s demand — “Don’t just sit there, do something” — by identifying something to worry about. This may or may not be the thing that made us anxious in the first place. It’s that lingering financial issue. It’s that recent social mishap. It’s the troubling state of world affairs . . .

- We then think about the worry topic (or identified threat) in a repetitive way, creating the illusion that we are preparing for threats.

Experiencing anxiety, then, is like encountering a problem: the problem of feeling threatened. And worrying creates the false impression that we are doing something to solve it. The result? Small-but-significant anxiety reduction and negative reinforcement.

Like excessive handwashing, worry also promotes itself through the Anxiety NONO. Imagine worrying about a loved one while she is out of town .“I hope she is OK. What if something terrible happened? How come she hasn’t called?” Our anxious brain twists and churns and spirals.

Several days later, after worrying and worrying, our loved one arrives home safely. Unfortunately, our brain connects excessive worry with her safe arrival:

I thought something bad might happen to my loved one.

+ So I worried about her.

+ Nothing bad happened to my loved one.

= Maybe nothing bad happened because I worried . . . better keep on worrying!

This is how most anxiety symptoms work. Behaviors like reassurance seeking, repetitive handwashing, and checking temporarily reduce anxiety, just as pressing a lever turns off a shock. This reduction — and feeling of “phew” that accompanies it — reinforces future avoidance.

Such behaviors also trick us into believing that our safety results from avoidance. Things are only OK because I sought reassurance. My relationship is only OK because I called over and over again. I’m only OK because I planned, prepared, and protected.

Together, the combined forces of negative reinforcement and the Anxiety NONO cause avoidance to snowball. Checking produces more checking. Preventative behaviors result in more preventative behaviors . . .

And worry leads to more worry.

Dylan M. Kollman, PhD

dkollman@realanxietysolutions.com